Containing the Spread of Ebola

by Kerry Connell

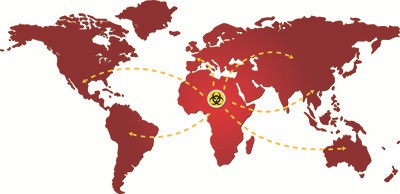

The recent Ebola outbreak in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone is all over the news, and, with cases also reported in Nigeria, Senegal, Spain, and the United States, awareness of this virus is at an all-time high. But despite the rumors and worries that accompany the fact-based journalism dedicated to Ebola, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) is keeping its collective head while preparing for the worst.

As with most diseases, prevention is better than a cure. The Ebola virus is extremely contagious, and the 2014 epidemic is the worst outbreak ever recorded. Adding to the concern is the high mortality rate: so far, approximately 70 percent of the people infected with Ebola in Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia have died. The total number of deaths has surpassed 4,800. Clearly, the best outcome for the United States would be to prevent the virus from establishing a foothold here.

On November 7, the CDC announced its purchase of $2.7 million of personal protective equipment to combat the spread of Ebola should any forthcoming case in the United States emerge as a credible threat. The equipment, which includes coveralls, aprons, boot covers, face shields, hoods, and respirators, is being packaged into 50 kits for delivery to hospitals that encounter a case of Ebola. The kits are considered part of the CDC's Strategic National Stockpile, a ready-to-go collection of medical supplies suited to public health emergencies.

Greg Burel, the director of the CDC's Strategic National Stockpile, notes that some of the items in the kits are not normally used for routine patient care in the hospital setting but that the agency is stocking up in the event that the supplies are needed. Each kit includes enough equipment for a medical team caring for a single Ebola patient for five days. Fewer than ten people in the U.S. have been diagnosed with Ebola, and several health care workers who had been treating patients in the countries bearing the brunt of the epidemic have returned to the States for treatment.

The agency previously issued official guidelines for caring for patients with Ebola. In hospitals or other healthcare settings, Ebola is transmitted through direct contact (through broken skin or mucous membranes of the eyes, nose, or mouth) with the blood or body fluids of a person who is infected with the virus. The infection also spreads through contact with objects (like needles or syringes) that have been contaminated with the virus. The CDC guidelines specify the use of personal protective equipment like fluid-resistant gowns, gloves, and masks and include instructions for both donning and removing protective garments in order to reduce the risk of contamination.

The CDC has specifically called out gear removal as the biggest risk factor for contamination. A breach in protocol is what led to the infection of a nurse in Dallas. Any infected fluid that makes it onto the surface of personal protective equipment could potentially spread to the caregiver upon removal of the garments. Certain techniques, like turning gloves inside out to remove them, can help to prevent the spread of the disease, but some situations can make careful use or removal more difficult. Heavy bleeding or copious amounts of other fluids demand immediate and full attention to the patient; caregivers may overlook a small gap in protective gear, or emergency conditions could lead to a need for additional equipment that was not anticipated.

Several small changes to routine can mitigate the danger, however. Requiring trained caregivers to observe their colleagues' donning their protective gear can catch slip-ups and mistakes like incomplete coverage of the hands and wrists. Double gloves, disposable shoe covers, or Tyvek suits can also help to prevent the spread of the virus. Frequent hand washing is also key—soap and water easily kill the Ebola virus.

The CDC has also specified repeated training procedures to ensure that caregivers know how to put on personal protective equipment quickly and correctly. Competence testing ensures that personnel who enter the room of any patient infected with the Ebola virus are able to perform all infection-control procedures. The requirements also mandate that a manager must oversee infection control procedures at all times if a patient with Ebola is present in the facility.

The CDC's recent purchase of personal protective kits, along with its stringent guidelines and a healthy respect for a virus that absolutely must be contained, bodes well for the United States in its response to the Ebola virus epidemic. Hysteria has no place in public health policy, but pragmatism and protection do.